As we anticipate an increasing population that is also increasingly wealthy, the conversation tends to focus on how much more food we’ll need to grow or how we can increase the yield of major crop staples. But, when it comes to feeding the planet, while producing more food will almost certainly be necessary, it won’t be enough. In rich and poor countries alike, the quality of the food we grow and eat may be even more important than the quantity.

In order to end hunger and malnutrition while achieving sustainable food production systems, we must not only feed people; we must also nourish them. Whether we can meet this goal depends heavily on the nature of our production systems, the variety of foods they produce, and the nutritional quality of that food.

Sustainable food production and healthy diets complement each other, each one providing a means and an end to achieving global food security.

This report focuses on the places where nutrient-rich foods are produced, as well as the farmers who produce them. The scope of the report includes crops, livestock, and fish products, as all play vital roles in ensuring nutritious diets around the world.

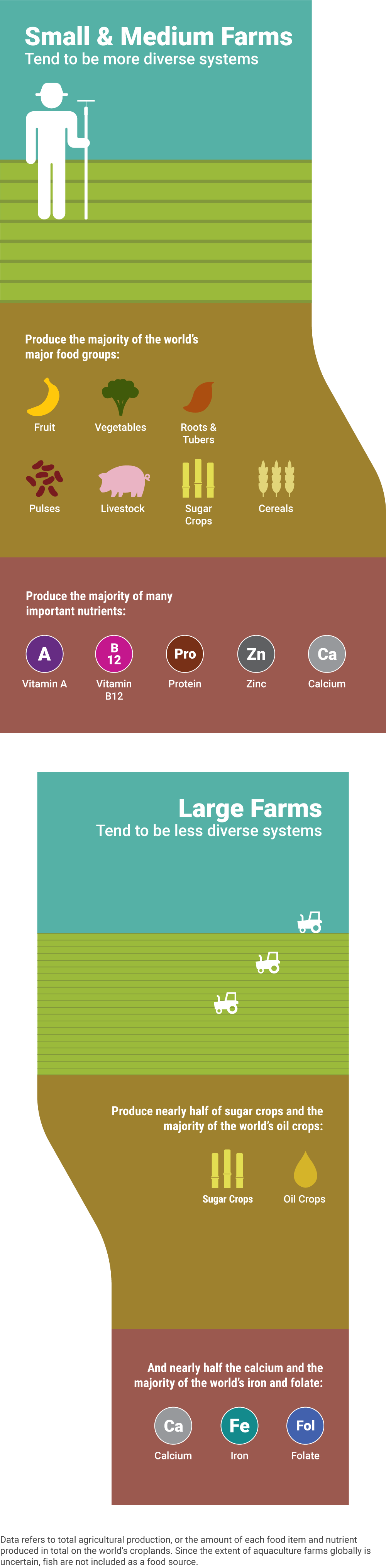

Globally, small and medium farms produce the majority of the foods and nutrients.

Photo: CAFOD Photo Library

Food is more than calories

We’re used to thinking of food in terms of calories—whether we are concerned about eating too much or not enough. However, food not only provides dietary energy; it is also the source of many different nutrients that play important roles in human growth and development, as well as disease prevention and longevity. Getting all the nutrients we need to grow, develop, and thrive requires eating a variety of foods.

Food diversity = nutrient diversity

A global triple threat

Malnutrition, in its various forms, exists in nearly every country in the world. The United Nations describes these forms of malnutrition as the “Global Triple Threat”:

- Hunger: Around 790 million people in the world don’t get enough calories to meet their needs. This number has declined from more than 1 billion people in the 1990s.

- Micronutrient deficiencies: Around 2 billion people in the world don’t get adequate vitamins or minerals in their diets, which can lead to poor growth and development in children and poor health in adults. This kind of malnutrition is often called “hidden hunger,” as its effects aren’t always visible to the naked eye.

- Overweight and obesity: Nearly 2 billion people in the world suffer from overweight or obesity related to excess calorie intake. This is also often associated with many chronic diseases affecting people around the world, from Type 2 diabetes to heart disease.

Malnutrition also has profound economic effects, arising from both lost productivity and the cost of treatment. This burden is felt more in some places than others, but overall leads to a loss equivalent to 10 percent of world GDP each year, or more than the global value lost during the 2008 financial crisis.

In an effort to both improve human wellbeing and reduce this economic burden, the UN is placing an increasing amount of attention and resources toward this issue. In fact, it is a key component of their Sustainable Development Goals, the second of which aims to end hunger and all forms of malnutrition by 2030.

Both small and large farms are critical for food security

Around the world, small and large farms play different but equally important roles in achieving food security.

Globally, small and medium farms of less than 50 hectares produce more than half (51-77 percent) of nearly all the foods and nutrients that are most central to our diet. This includes the majority of the world’s roots and tubers, vegetables, fruit, pulses, cereals, and livestock.

The pattern is similar for global nutrients: small and medium farms produce more than half of nearly all nutrients examined here, with the exception of folate and iron. They also account for an especially large proportion of vitamin A (77 percent). In comparison, small and medium farms contribute 57 percent of global food calories.

On the other end of the spectrum, large farms of more than 50 hectares produce 30-64 percent of the world’s major food types. This includes 64 percent of oil crops, and nearly half (49 percent) of cereals. While cereals and oil crops are less nutrient-dense and often have lower bioavailability of some micronutrients than other foods considered, the scale and efficiency of their production mean that large farms are major contributors of key micronutrients at the global scale. In addition, the surplus of food produced on large farms provide vital calories for trade to address scarcity in many parts of the world.

Although large farms produce just 43 percent of the world’s total calories, they produce the majority of the world’s folate (56 percent) and iron (55 percent). They also account for nearly half of the world’s calcium (49 percent), protein (48 percent), and zinc (47 percent).

Smaller farms are dominant providers of nutrition in developing countries, while large farms often provide much-needed surpluses to address global scarcity.

Photo: WorldFish

The role of farm size differs around the world

While small farms exist in a vast array of different agricultural systems across the planet, the role these farms play differs depending on where in the world you are. In developing or middle-income nations, small farms are the critical provider of micronutrients for the food supply, especially for many of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people.

Foods

Nutrients

Farm Size

- Very small

- Small

- Medium

- Large

- Very large

- 1% of world

production

Small farms produce more than three quarters of most foods in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and China. In addition, small farms produce more than 80 percent of essential nutrients in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, South Asia, China, and the rest of East Asia Pacific.

In Asia, the vast majority of farming happens in densely populated landscapes made up of many small farms. Very small farms (less than 2 hectares) produce more than half of all nutrients in China, and over a quarter of nutrients in many other regions, including South Asia, Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and East Asia Pacific.

It’s important to note that some foods are not major global sources of nutrient production, but are critical to regional food security. Fish, for example, is a minor contributor of calories and protein worldwide, but supplies a fifth of vitamin B12 in China and Southeast Asia.

Most of sub-Saharan Africa is dominated by smallholder farming, though in many cases systems are less dense as farms use less productive or more arid land for grazing livestock and other practices. Often, these areas are also characterized by a greater nutritional dependence on local production, due to a lack of access to markets, as well as transportation and storage infrastructure, and a focus on minimizing risk and variability. In such parts of the world, small farms are responsible for about 80 percent of essential nutrients produced in each region, as well as more than 60 percent of regional food calories.

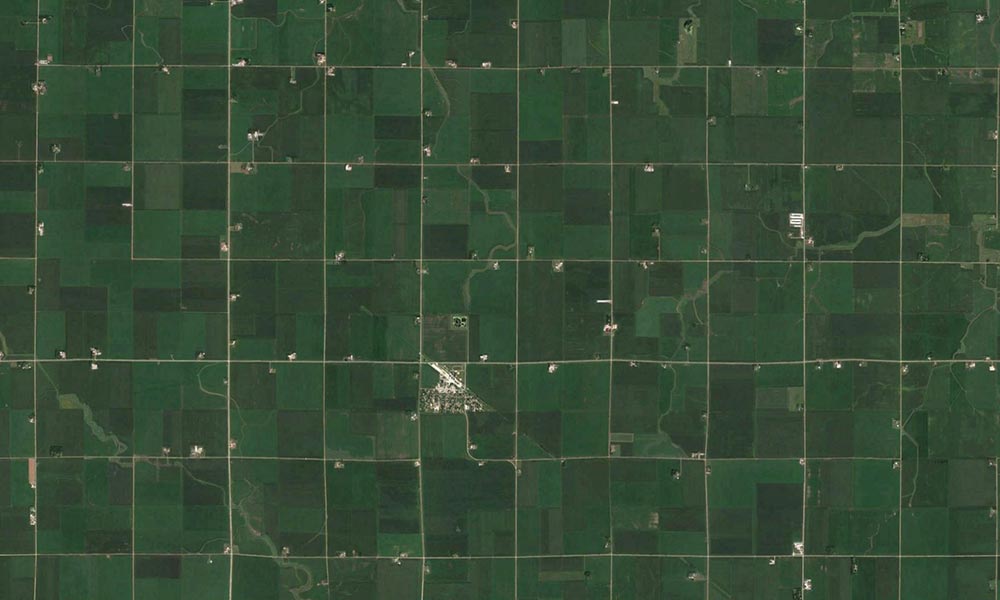

At the same time, large farms dominate production in North America, South America, Australia, and New Zealand. In these regions, large farms account for nearly all (75-100 percent) of cereal, livestock, and fruit production. In South America, Australia, and New Zealand, very large farms account for more than half of nutrients produced.

In Europe, West Asia, North Africa, and Central America, medium-sized farms contribute a more significant proportion of foods and nutrients.

Explore farm size patterns further with our interactive story map.

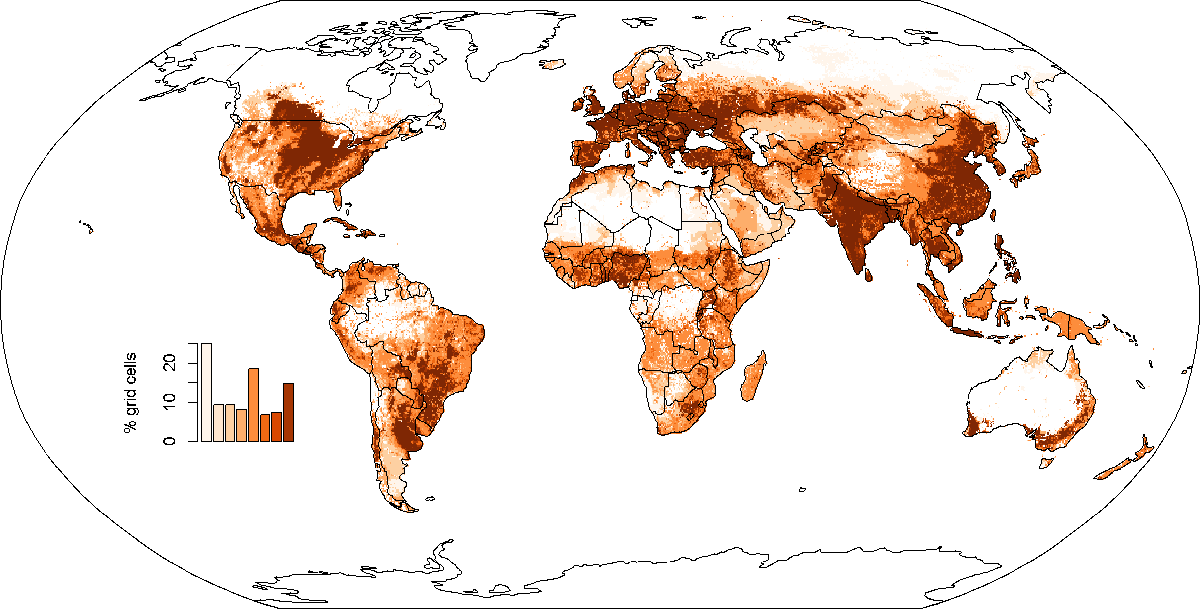

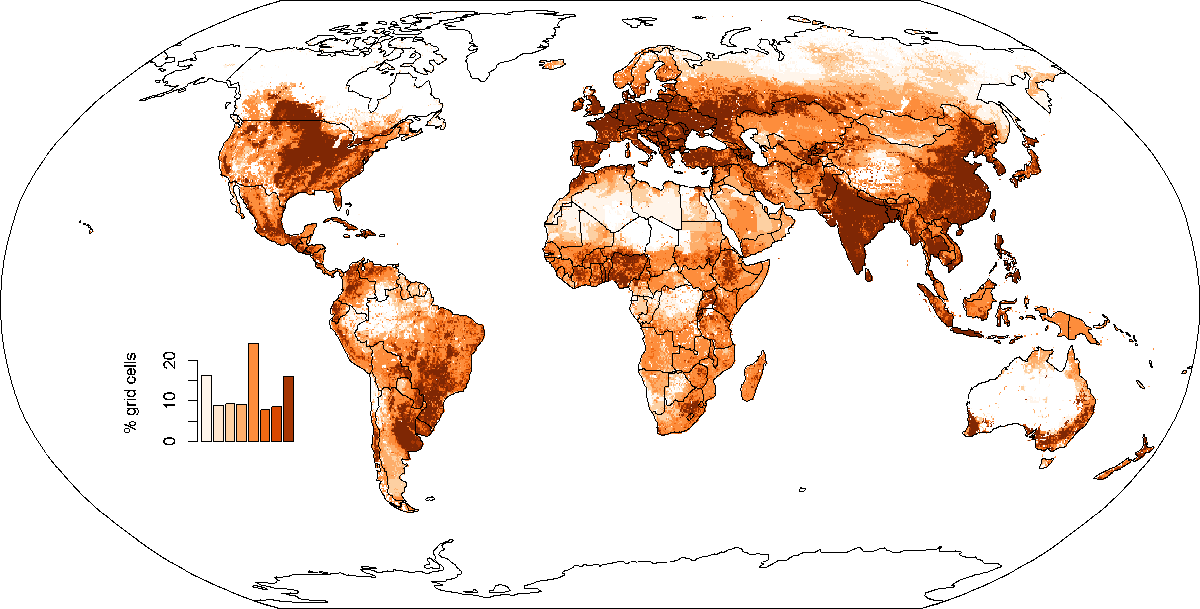

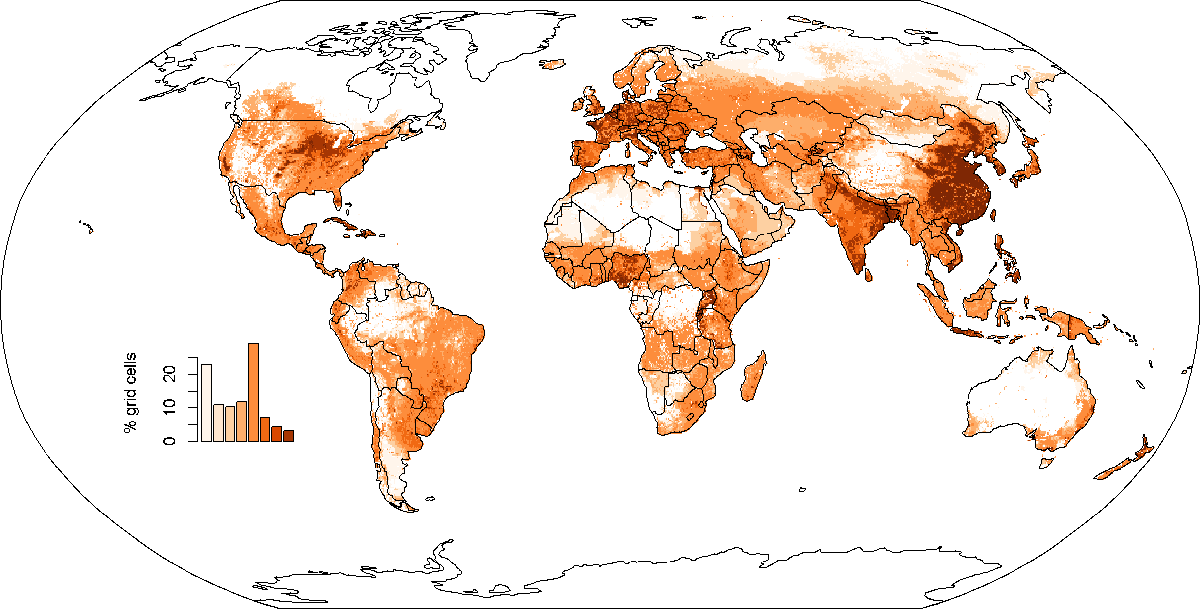

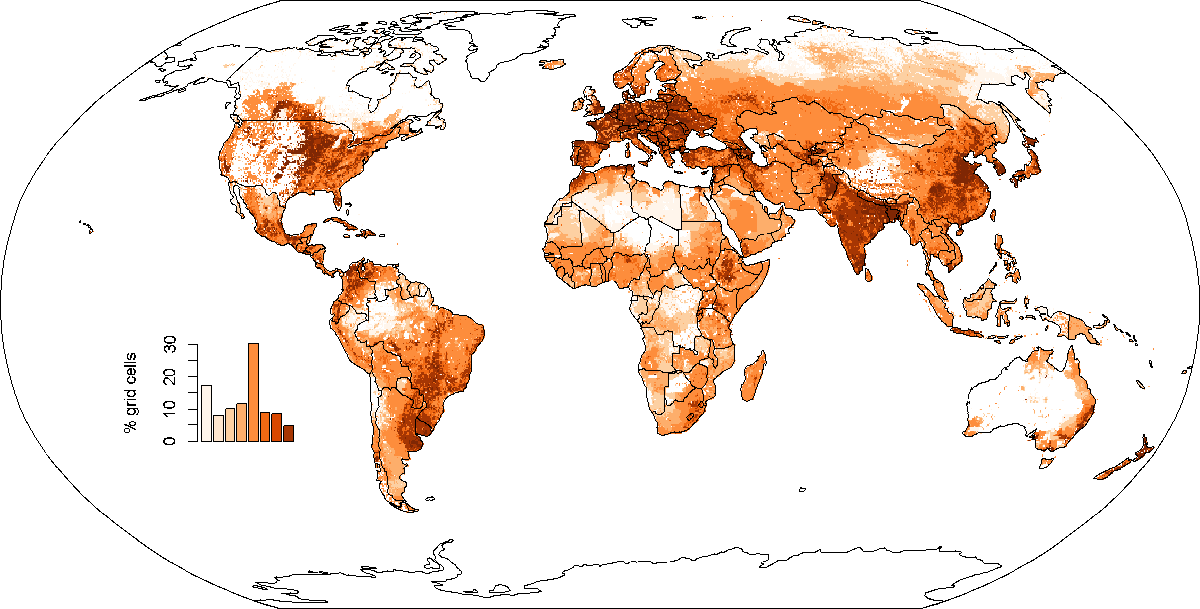

Our nutrient-dense world

The maps below show nutritional yields, or the number of people who can meet their nutritional needs from all of the crops, livestock, and fish grown in an area. Global hotspots include China, India, Europe, the North American Great Plains, Southern Brazil and Northern Argentina, the East African highlands, and parts of West Africa.

Since vitamin A and vitamin B12 are supplied by fewer commodities, their global production is lower and limited to a few key areas.

Small farms depend on diversity

In order to improve human wellbeing around the world, while also maintaining diverse and healthy agroecosystems, we must reassess our goals. Rather than simply feeding people, we need to think about nourishing people with diverse foods.

Diversity and balance in food systems are good for people and ecosystems. Small farms often exist as part of diverse agricultural landscapes that support a wide variety of crop and non-crop species. The results are often a mosaic of crops, trees, and pastures.

In addition to making up more diverse landscapes, small and medium-sized farms include greater levels of crop species and genetic diversity than do larger farms. This diversity can improve the resilience of farming systems.

For example, since shocks may affect some crops or livestock more than others, a diverse farm can provide a buffer to extreme weather events, price fluctuations, or pests and disease. Diversity on farms can also help ensure a supply of nutritious food that is available at different seasons throughout the year. Moreover, small farms often have greater crop productivity per unit area than large farms.

Even though highly diverse farms occupy less area, they produce the majority of the world’s nutrient-dense foods. Farms that are highly diverse produce 80 percent of the world’s vegetables, 70 percent of roots and tubers, 67 percent of pulses, 60 percent of livestock, and 58 percent of cereals. Higher agricultural diversity generally leads to greater diversity of micronutrients.

As with farm size, agricultural diversity of various regions differs around the world. For example, much of the western part of South America, Asia, Africa, and Europe produce a lot of different foods. In contrast, much of Australia, and North and South America are not agriculturally diverse, producing relatively fewer types of crops, livestock, and fish.

Explore further with our interactive story map. All slideshow photos courtesy of Google Earth.

Solutions

Are smaller farms stewards of global nutrition? The answer is a resounding yes. At the same time, though, large farms are critical to global food security. To truly improve the quality of the food we produce, and not just ensure adequate calories, effective solutions must be rooted in a regional understanding of how the size of farm systems influences food and nutrient production.

In parts of the world where farmers and communities have limited access to markets, growing a broad range of nutrient-rich foods on local farms is essential to a diverse and healthy diet. Intensification strategies that lead farmers to cultivate fewer crops—often just a few cereals and pulses—will have negative effects on the health of people and the resilience of the agricultural system. In these systems, producer-focused solutions are necessary to enable farmers to cultivate diverse and resilient systems.

Agricultural diversity is important in wealthier countries as well. Robust markets and widespread trade enable a broad range of food choices, but do not necessarily support healthy diets or diverse agricultural systems. The prevalence and affordability of processed foods—made up of just a few food types such as corn, soy, and beef—can lead to malnutrition and obesity even where food is plentiful.

While people can access a diversity of crops via supermarkets, the lack of diversity in large, intensified farming systems can make countries less resilient to climatic variation or pests, requiring environmentally harmful inputs and methods to be productive. In these systems, both consumer-focused and producer-focused solutions are needed to support sustainable and nutritious food systems.

Small indigenous fish

In Bangladesh, farmers are reducing vitamin A deficiency in their communities with a novel approach that relies on a small indigenous fish species in homestead ponds. Farmers here usually raise a few species of large carp to be sold profitably at market. However, mola—a small, indigenous fish—provides ample vitamin A and other micronutrients including iron, zinc, and calcium. Large fish are typically harvested only once or twice during a production season, while mola can be harvested throughout the season to be sold at market or used for home consumption. As a result, farmers’ production and income increases, along with the nutritional value of production.

Village-level diversity

Much of the discussion about diversification focuses on individual farms. While there is advantage to diversification to reduce risk, for small farms it also eliminates most of the benefits that come with specialization (and scale). It is useful to think about diversification at scales other than the farm. Diversification at the village level can provide a more diverse local food supply in areas that have less effective markets, and also allows some degree of specialization at the level of individual farms. The Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) Climate-Smart Villages is one example of an effort to support agricultural diversity at the village scale.

Subsidizing the costs of produce

In industrialized economies like the United States, the discussion of subsidies to improve health has been largely focused on production. There is a good reason that fruit and vegetable growers tend to oppose this strategy: it encourages competition in that sector, which drives down prices, so the economic condition of current growers may deteriorate. As consumption is arguably the largest driver of industrialized food systems, subsidizing fruit and vegetable consumption could significantly improve access to healthy foods. In the U.S., subsidies for fruit and vegetables through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children were seen to increase consumption even after the program was finished.

Develop more nutritious crop varieties and animal breeds

Currently, many crop-breeding programs focus on improving a few major food commodities. However, nutrition can be integrated into both public and private crop breeding projects. This could reverse a long-term trend away from public support of crop breeding, and in particular a limited range of crops and livestock. Currently, there are a number of NGOs and scientific societies pushing projects like these forward, including the Open Source Seed Initiative and Bioversity International.

Writing and editorial review: Barrett Colombo, Jessica Bogard, Paul West, Leah Samberg, Mario Herrero, James Gerber, Peder Engstrom.

The following people provided data and helpful review: Timothy Griffin (Tufts), Brendan Power (CSIRO).

Design: smashLAB.

Environment Reports: Briefings on the most pressing environmental challenges facing the world today. Published by the Institute on the Environment at the University of Minnesota, Environment Reports is a collaboration between an international group of scientists, writers, and designers to combine incisive narratives about environmental challenges… Read More

Sources

- Alexandratos, N. & Bruinsma, J. World Agriculture Towards 2030/2050: The 2012 Revision. (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2012).

- Altieri, M. A., Funes-Monzote, F. R. & Petersen, P. Agroecologically efficient agricultural systems for smallholder farmers: contributions to food sovereignty. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 32, 1–13 (2012).

- Bogard, J. R. et al. Nutrient composition of important fish species in Bangladesh and potential contribution to recommended nutrient intakes. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 42, 120–133 (2015).

- Deininger, K. & Byerlee, D. The Rise of Large Farms in Land Abundant Countries: Do They Have a Future? World Development 40, 701–714 (2012).

- Englberger, L. et al. Carotenoid and riboflavin content of banana cultivars from Makira, Solomon Islands. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 23, 624–632 (2010).

- FAO & WHO. Vitamin and mineral requirements in human nutrition: report of a joint FAO/WHO expert consultation. (Food and Agriculture Organization, World Health Organization, 2004).

- Fiedler, J. L., Lividini, K., Drummond, E. & Thilsted, S. H. Strengthening the contribution of aquaculture to food and nutrition security: The potential of a vitamin A-rich, small fish in Bangladesh. Aquaculture 452, 291–303 (2016).

- Frelat, R. et al. Drivers of household food availability in sub-Saharan Africa based on big data from small farms. PNAS113, 458–463 (2016).

- Haddad, L. et al. A new global research agenda for food. Nature News 540, 30 (2016).

- Hazell, P., Poulton, C., Wiggins, S. & Dorward, A. The Future of Small Farms: Trajectories and Policy Priorities. World Development 38, 1349–1361 (2010).

- Herrero, M. et al. Biomass use, production, feed efficiencies, and greenhouse gas emissions from global livestock systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, 20888–20893 (2013).

- Herrero, M. et al. Farming and the geography of nutrient production for human use: a transdisciplinary analysis. The Lancet Planetary Health 1, e33–42 (2017).

- Hertel, T. W., Ramankutty, N. & Baldos, U. L. C. Global market integration increases likelihood that a future African Green Revolution could increase crop land use and CO2 emissions. PNAS 111, 13799–13804 (2014).

- Joint WHO/FAO/UNU Expert Consultation. Protein and amino acid requirements in human nutrition. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1–265, back cover (2007).

- Khoury, C. K. et al. Increasing homogeneity in global food supplies and the implications for food security. PNAS 111,4001–4006 (2014)

- Lowder, S. K., Skoet, J. & Singh, S. What do we really know about the number and distribution of farms and family farms worldwide?. (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2014).

- Merrigan, K. et al. Designing a sustainable diet. Science 350, 165–166 (2015).

- Nino, F. S. Hunger and food security. United Nations Sustainable Development

- Remans, R. et al. Assessing Nutritional Diversity of Cropping Systems in African Villages. PLOS ONE 6, e21235 (2011).

- Remans, R., Wood, S. A., Saha, N., Anderman, T. L. & DeFries, R. S. Measuring nutritional diversity of national food supplies. Global Food Security 3, 174–182 (2014).

- Research Institute (IFPRI), I. F. P. 2016 Global hunger index: Getting to zero hunger. (International Food Policy Research Institute, 2016).

- Samberg, L. H., Gerber, J. S., Ramankutty, N., Herrero, M. & West, P. C. Subnational distribution of average farm size and smallholder contributions to global food production. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 124010 (2016).

- Sukhdev, P., May, P. & Müller, A. Fix food metrics. Nature News 540, 33 (2016).

- Thilsted, S. H. & Wahab, M. A. Polyculture of carps and mola in ponds and ponds connected to rice fields. (CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems, 2014).

- West, P. Mind the gaps: Reducing hunger by improving yields on small farms. The Conversation. (Accessed: 3rd February 2017)

- Global Nutrition Report 2016: From Promise to Impact: Ending Malnutrition by 2030. (International Food Policy Research Institute, 2016).

- The State of Food and Agriculture 2016. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2016). (Accessed: 3rd April 2017)

- Cooked or raw, Fei’i bananas are delicious and nutritious. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations(2016). (Accessed: 4th March 2017)

- USDA Food Composition Database. (2017). (Accessed: 31st March 2017)

- Food systems and diets: facing the challenges of the 21st century. Global Panel. (Accessed: 8th March 2017)

- Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. (Accessed: 3rd April 2017)